A crackdown on paid puffery

It all began with a complaint to the BC Securities Commission (BCSC) from a disgruntled former business associate of a local company.

It ended – sort of – seven years later, with a string of settlements and sanctions against six individuals and four companies, and a new set of expectations in British Columbia about a stubbornly troublesome feature of the investment market: Stock promotion.

A time-tested practice turbo-charged by technology

Touting stocks is a practice nearly as old as the stock market, especially in venture markets like B.C.’s. Such markets are populated by small, relatively unknown companies, most of which are pursuing legitimate but high-risk business plans, and they will starve and die without regular infusions of new capital from investors. To generate interest, these companies often hire experienced promoters to raise their profile. But there has always been a small set of companies focused mostly on boosting their stock price so they can earn a quick buck in the market. And there have always been promoters all too willing to help them.

For decades, promotion was done through printed newsletters and flyers filled with “hot tips.”

A social media post that lacked “clear and conspicuous” |

Then came the internet.

Not only did the volume of information explode, but it became easier to create and publish promotional material – articles, blog posts, social media posts, podcasts, “finfluencer videos” – that had an aura of news or independent commentary. If readers and viewers couldn’t easily detect that the content was bought and paid for, they might lend it more credence than it deserved and make misguided investments.

The former business associate who contacted the BCSC in 2017 had a variety of complaints, many of which were outside the BCSC’s jurisdiction. But one of them concerned this burgeoning type of stock promotion.

“Clearly and conspicuously” (not)

The company’s CEO had sent a mass email to shareholders, highlighting a flattering story about it on a website called the “FinancialPress.com.” The email’s unmistakable message: Here was evidence that his company remained a good investment.

The former business associate was vexed that the story highlighted in the email was not an arm’s-length assessment by an independent source. It was commissioned by the company itself; it was advertising disguised as information.

BCSC lawyers quickly realized that the complaint might be valid, because B.C.’s Securities Act requires that promotional material “clearly and conspicuously” disclose that it was created and disseminated on behalf of a company or shareholder. The article lacked any such statement.

Following the money

The BCSC’s first step was to learn more about the flattering article. The business associate pointed the BCSC to a Vancouver-based investor relations (IR) firm called Stock Social Inc. So the BCSC ordered it to provide any records of a connection it had with “Financial Press.com” and the author of the article.

Stock Social acknowledged it was the owner of the “Financial Press.com,” and that it had a contract with the company to provide investor relations services. So the BCSC asked for all records relating to that business relationship, and if it had other clients.

It did – about a dozen.

“It kind of exploded from there,” said Joel Hill, then a Senior Compliance Officer in the BCSC’s Division of Corporate Finance.

The BCSC contacted Stock Social’s clients, and found that many of them were using multiple IR firms, besides Stock Social, to create buzz around their market value.

|

A scene from a promotional video for Stock Social Inc. |

“A much bigger problem”

So Hill and his team then went to those other IR firms, and found that they, too, had client lists as large or larger – sometime far larger – than Stock Social did. And all of them were indulging in some form of chicanery: promotional articles that lacked “clear and conspicuous” disclaimers that the articles were produced on behalf of the featured companies.

The BCSC’s production orders – legally binding demands for records – kept coming, yielding more evidence of a thriving promotional business.

“We realized this was a much bigger problem,” said Hill, now the Manager of Compliance in Division of Corporate Finance. “Once we knew to look for something, we started seeing it all over the place.”

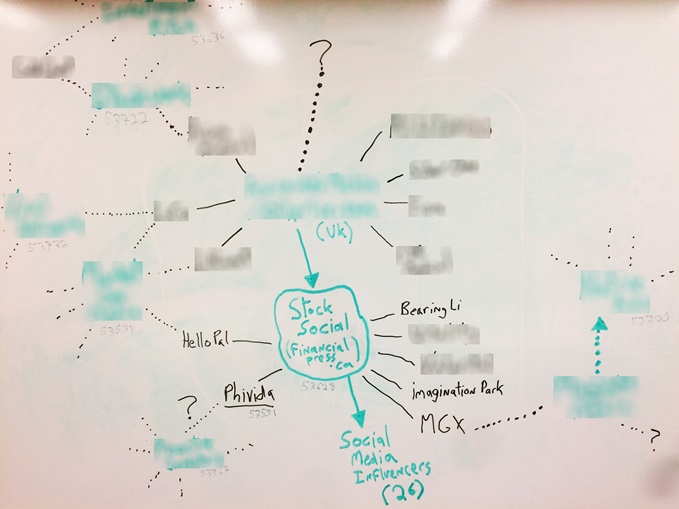

As the records piled up, Hill retreated one day to a BCSC meeting room with a wall-length whiteboard. Like one of those movies where the dogged investigator sketches out a web of criminal conspirators, he filled the whiteboard with names of the various IR firms, the far more numerous corporate clients, and the connections among them.

Instead of a criminal conspiracy, Hill diagrammed a profusion of puffery: seven IR firms (five in Vancouver, one in Toronto and one in the U.K.) that disseminated records for hundreds of B.C. companies over the previous six years. One company acknowledged having arrangements with 27 firms to promote its stock in the previous year.

|

Joel Hill’s whiteboard diagram showing the web of connections between companies and promotional firms. |

A spectrum of negligence

The lack of disclosure attached to the articles, blog posts, social media posts and videos of these IR firms was rampant. But there were differences of degree:

- Some had no disclosure at all.

- Some disclosure was vague, along the lines of, “We may have received compensation from a company for this,” without specifying who that might be.

- Some disclosure was clear, but not conspicuous, because it was buried in a footnote, in small font, in the middle of dense legal-ese that almost no one ever reads, or was relegated to another linked page.

While most of it, in the view of BCSC staff, violated the law, pursuing legal action against all of the entities on Hill’s diagram would have consumed too many resources and taken many additional years. Instead, they decided to pursue a “test case” that would draw a bright red line about what is and is not legal, and send a message to IR firms and companies that paid for promotion.

BCSC staff focused on the firm that sparked the investigation: Stock Social. In 2021, BCSC staff filed formal allegations against Stock Social and its president, CEO and sole director Kyle Alexander Johnston, and against five companies (and individuals associated with each of those companies) that hired Stock Social.

|

A year later, the BCSC entered into settlement agreements with five Stock Social clients, resulting in payments to the BCSC of $10,000 to $35,000. The allegations against Stock Social were heard by a BCSC panel, which found that the firm and Johnston had violated the Securities Act, ordering the firm to pay $50,000 and Johnston to pay $25,000. (He is now deceased.)

Prominent spots, prominent fonts

The settlements and panel decision gave the BCSC staff what they needed – not only a finding of illegal activity and orders that could deter others from doing the same, but also a detailed explanation from a securities regulatory panel as to what kind of disclosure is expected.

With that decision in hand, BCSC staff issued a special notice laying out its expectations for such promotional material. For example:

- It should say it was “disseminated on behalf of” the company, or is a “paid advertisement on behalf of” the company.

- The statement should appear in a prominent spot, and not be consigned to a separate, linked page.

- The statement “should not be buried in legalistic standard terms and conditions that readers often skip.”

- The statement should appear in a prominent font.

“Most people want to comply, but they also want certainty about what they need to comply with,” Hill said. “They want someone to say, ‘You can do this, you can’t do that.’ Now we can be very clear when telling people what we consider to be adequate disclosure.”

A more transparent approach to promotion

Armed with the Stock Social decision and the subsequent notice, the BCSC invited IR firms to information meetings about the law and BCSC compliance expectations. Hill has since noticed significant improvement.

“The overall quality of the disclosure is much better than it was before Stock Social,” he said. “It seems there is almost always a disclaimer now, and the disclaimers are more visible. Investors can now see that, and take it into account.”

The ramifications of Stock Social could soon extend beyond British Columbia. The BCSC and the other Canadian securities regulators are developing new, codified and consistent rules about disclosure of promotional activities that would apply in every province and territory.

If enacted, those rules could be traced back nearly a decade – to a disgruntled business associate, a flattering article, motivated regulatory staff, and a cluttered whiteboard.

|